The Republican Urinal

Visitors caught short in Alcalá will search in vain for a public convenience, but ´twas not ever thus. During the short-lived Second Republic of the 1930s, the town's socialist administration provided the good people of Alcalá with a number of facilities previously lacking: a museum, a covered market, a library, and a public urinal. However, it was nearly as short-lived as the Republic itself.

Here is its story (an abridged translation of an article by Jaime Guerra Martinez on the Historia de Alcalá de los Gazules blog).

Here is its story (an abridged translation of an article by Jaime Guerra Martinez on the Historia de Alcalá de los Gazules blog).

|

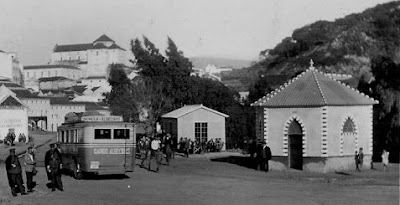

| The hexagonal public conveniences, a short hop from the bus stop |

What

disappointment was suffered

By the sons of our

city

Over the public

urinal

Built opposite Bernal's

This verse, sung

by a band of street musicians during Alcalá's Carnival in the 1930s,

reflected the popular reaction among the less prudish citizens to the

introduction of a charge for using the recently-opened public urinal

in what was then the Paseo de la República.

The urinal was a symbol of liberty

for some, offering an essential public

service and demystifying a natural physiological necessity, while for others it was affront to decency,

bringing into public view something which should be done at home.

But one has to wonder how many houses had adequate facilities for

such functions, apart from the tin bucket in which the “doings of

the stomach” were kept until nightfall, zealously protected from

the flies.

Either way, what is certain is that our public convenience was born,

lived and died during the most hazardous decade of 20th century Spain, the 1930s. Today it survives only in the memories of

the elderly, a few photographs and the not insignificant records held

in our Municipal Archive, which I choose bring to light to indulge my curiosity over what went on in that ill-fated hexagon, what was written on its walls, what comments and presumptions were ingrained in its encrusted yellowing basins ....

The work was part

of a group of construction projects carried out under the local

Republican administration to improve the infrastructure and

facilities of the town. It was agreed to build a

“lavatory” opposite the house of Don Domingo Bernal on the Paseo

de la República [now the Paseo de la Playa]. It was built in the

spring of 1932, in the form of a hexagon whose sides corresponded

with the six urinals inside. It was finished with decorative

brickwork, in a reasonably harmonious vernacular style.

Nevertheless its

location wasn't ideal, and the level of cleaning wasn't

up to scratch, provoking irate protests from various citizens, some

of whom regarded as too public certain things that ought to be more

private. The objections came to a head when users were obliged to pay

a charge towards its maintenance and the cost of an attendant.

So in September 1933 Don Andrés Jobacho, master builder,

wrote to the council offering to demolish it and replace it with an

underground one nearby, in exchange for the materials used for

the original. The reasons given were the lack of hygiene, the loss of

visibility from the Paseo, and the unaesthetic appearance and layout

of the hexagon. The new location would be underneath a house he was building, which

later became a shop [today it is the Cafeteria Siglo XXI].

|

| Andrés Jobacho's proposed underground loos |

The council appointed a Committee to report on the proposal, which found some important details were missing. Jobacho was given the opportunity to revise it, and in February 1934 he delivered a new plan

of the underground toilets, with separate cubicles for men and

women, using the existing materials, sewerage disposal and water supply.

On

7 February Jobacho's proposal was approved, with just one opposing vote, a local builder called Gaspar Muñoz, who had pointed out the shortcomings in the original proposal.

By September Jobacho had all his permits, including the approval of

the National Body of Engineers for Roads, Canals and Ports of the

Province of Cadiz, and the Town Hall gave its authorisation on 26 September 1934.

|

| The new toilets would have been underneath the building in the foreground, now Siglo XXI |

Nevertheless,

the hexagonal urinal was not pulled down and neither was the

underground one built. The reason was the change in Alcalá's

[socialist] municipal government after the victory of CEDA [Spanish

Confederation of the Autonomous Right] in the October 1934

elections.

In March 1938 it was proposed to build a new installation on the

corner between the bull-ring and Calle Sánchez Flores, on a plot

where a ruined house had been demolished. It would have six toilet

compartments and the tiles from the original construction would be

re-used. The budget rose to 1407 pesetas.

|

| The 1938 plan, which never came to fruition |

But

this project did not go forward either, temporarily prolonging the life

of the much-maligned hexagon. On 9 June 1938 it was agreed that the “kiosk of

necessities” should instead be turned into a bar or cafe, and the

proceeds from its lease would contribute towards the planned indoor

market. But the resolution was not well received and there were no

takers for the lease, mainly because they would have to refurbish the

building themselves.

Seeing the writing on the wall, Juan Cubo Cid, the attendant, requested retirement (not before time - he was 87). His request was approved, the Management

Committee abolished the post and the facility was closed.

On

29 December 1941 it was agreed to proceed with its

demolition, a job which was given to Gaspar

Muñoz Márquez, the builder who had voted against the original construction, who bought the materials for 450

pts.

This

finally brought an end to the controversy, breaking definitively with

that symbol which at that point in history had to be removed at any cost – the

Republican urinal.

Comments